TAU archaeologists find 4,500-year-old fingerprints on children’s artifacts

Pottery and figurines reveal traces of children as young as seven and eight

Support this researchArchaeologists from Tel Aviv University (TAU) and the National Museum in Copenhagen analyzed 450 pottery vessels made in Tel Hama, a town at the edge of the Ebla Kingdom, one of the most important Syrian kingdoms in the Early Bronze Age (about 4,500 years ago), and found that two-thirds of the pottery vessels were made by children, starting at the ages of seven and eight.

They also found evidence of the childrens’ independent creations outside an industrial framework, which illustrate the spark of childhood even in early urban societies.

The research was led by Dr. Akiva Sanders, a Dan David Fellow at TAU’s Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities. The findings were published on July 25, 2024, in the journal Childhood in the Past.

“Our research allows us a rare glimpse into the lives of children who lived in the area of the Ebla Kingdom, one of the oldest kingdoms in the world,” Dr. Sanders says. “We discovered that at its peak, roughly from 2400 to 2000 BCE, the cities associated with the kingdom began to rely on child labor for the industrial production of pottery. The children worked in workshops starting at the age of seven and were specially trained to create cups as uniformly as possible, cups which were used in the kingdom in everyday life and at royal banquets.”

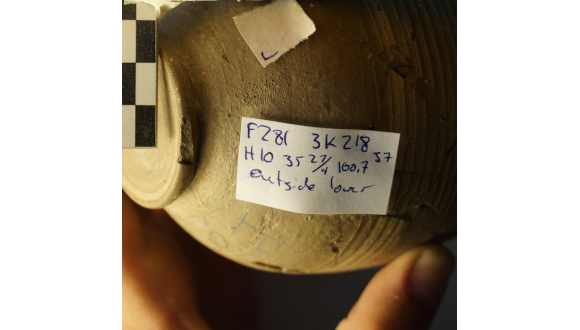

A person’s fingerprints do not change throughout their life. For this reason, the size of the palm can be roughly deduced from measuring the density of the margins of the fingerprint. From the size of the palm, the age and sex of the person can estimated. The pottery from Tel Hama, on the southern border of the Kingdom of Ebla, was excavated in the 1930s, and since then has been kept in the National Museum in Denmark.

As a result of the analysis of fingerprints on this pottery, researchers believe that most of it was made by children. In the city of Hama city, two-thirds of the pottery was made by children. The remainder was created by older men.

“At the beginning of the Early Bronze Age, some of the world’s first city-kingdoms arose in the Levant and Mesopotamia,” says Dr. Sanders. “We wanted to use the fingerprints on the pottery to understand how processes such as urbanization and the centralization government functions affected the demographics of the ceramic industry. In the town of Hama, an ancient center for the production of ceramics, we initially see potters around the age of 12 and 13, with half the potters being under 18, and with boys and girls in equal proportions.

“This statistic changes with the formation of the Kingdom of Ebla, when we see that potters were starting to produce more goblets for banquets. And since more and more alcohol-fueled feasts were held, the cups were frequently broken and more cups needed to be made. Not only did the Kingdom begin to rely more and more on child labor, but the children were trained to make the cups as similar to each other as possible. This is a phenomenon we also see in the industrial revolution in Europe and America: it is very easy to control children and teach them specific movements to create standardization in handicrafts.”

However, there was one bright spot in the children’s lives: making tiny figurines and miniature vessels for themselves. “These children taught each other to make miniature figurines and vessels, without the involvement of the adults,” says Dr. Sanders. “It is safe to say that they were created by children, and probably including those skilled children from the cup-making workshops. It seems that in these figurines the children expressed their creativity and their imagination.”