CRISPR therapeutics can damage the human genome, TAU researchers warn

Study finds genome editing method is very effective, but not always safe

Support this researchA new study from Tel Aviv University (TAU) identifies risks in the use of CRISPR therapeutics, the innovative, Nobel-prize-winning method that involves cleaving and editing DNA, already employed for the treatment of conditions like cancer, liver and intestinal diseases, and genetic syndromes. The researchers detected a loss of genetic material in up to 10% of the treated cells and explain that such loss can lead to destabilization of the genome, which might lead to cancer.

The study was led by Dr. Adi Barzel of the School of Neurobiology, Biochemistry and Biophysics at TAU’s Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and Dotan Center for Advanced Therapies, a collaboration between the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (Ichilov) and TAU, and by Dr. Asaf Madi and Dr. Uri Ben-David from TAU’s Faculty of Medicine and Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics. The findings were published on June 30, 2022, in Nature Biotechnology.

CRISPR is a groundbreaking technology for editing DNA, cleaving DNA sequences at certain locations in order to delete unwanted segments, or alternately repair or insert beneficial segments. Developed about a decade ago, the technology has already proved impressively effective in treating a range of diseases, including cancer, liver diseases, and genetic syndromes. The first approved clinical trial ever to use CRISPR was conducted in 2020 at the University of Pennsylvania, when researchers applied the method to T-cells (white blood cells of the immune system). Taking T-cells from a donor, they expressed an engineered receptor targeting cancer cells while using CRISPR to destroy genes coding for the original receptor. Otherwise, the receptor might have caused the T-cells to attack cells in the recipient’s body.

In the present study, the researchers sought to examine whether the potential benefits of CRISPR therapeutics might be offset by risks resulting from the cleavage itself, assuming that broken DNA is not always able to recover.

“The genome in our cells often breaks due to natural causes, but usually it is able to repair itself, with no harm done,” Dr. Ben-David and his research associate Eli Reuveni explain. “Still, sometimes a certain chromosome is unable to bounce back, and large sections, or even the entire chromosome, are lost. Such chromosomal disruptions can destabilize the genome, and we often see this in cancer cells. Thus, CRISPR therapeutics, in which DNA is cleaved intentionally as a means for treating cancer, might, in extreme scenarios, actually promote malignancies.”

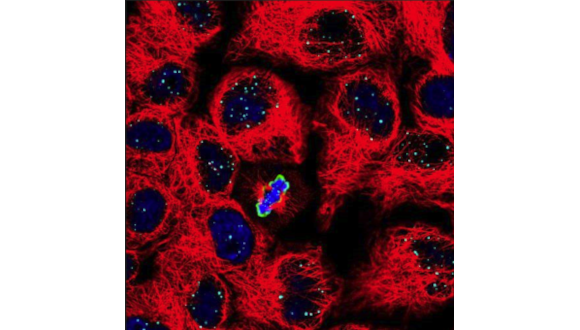

To examine the extent of potential damage, the researchers repeated the 2020 Pennsylvania experiment, cleaving the T-cells’ genome in exactly the same locations – chromosomes 2, 7, and 14 of the human genome’s 23 pairs of chromosomes. Using a state-of-the-art technology called single-cell RNA sequencing, they analyzed each cell separately and measured the expression levels of each chromosome in every cell.

A significant loss of genetic material was detected in some of the cells. For example, when Chromosome 14 had been cleaved, about 5% of the cells showed little or no expression of this chromosome. When all chromosomes were cleaved simultaneously, the damage increased, with 9%, 10%, and 3% of the cells unable to repair the break in chromosomes 14, 7, and 2 respectively. The three chromosomes did differ, however, in the extent of the damage they sustained.

“Single-cell RNA sequencing and computational analyses enabled us to obtain very precise results,” Dr. Madi and his student Ella Goldschmidt say. “We found that the cause for the difference in damage was the exact place of the cleaving on each of the three chromosomes. Altogether, our findings indicate that over 9% of the T-cells genetically edited with the CRISPR technique had lost a significant amount of genetic material. Such loss can lead to destabilization of the genome, which might promote cancer.”

Based on their findings, the researchers caution that extra care should be taken when using CRISPR therapeutics. They also propose alternative, less risky methods for specific medical procedures, and recommend further research into two kinds of potential solutions: reducing the production of damaged cells, or identifying damaged cells and removing them before the material is administered to the patient.

“Our intention in this study was to shed light on potential risks in the use of CRISPR therapeutics,” Dr. Barzel and his PhD student Alessio Nahmad conclude. “We did this even though we are aware of the technology’s substantial advantages. In fact, in other studies we have developed CRISPR-based treatments, including a promising therapy for AIDS. We have even established two companies, one using CRISPR and the other deliberately avoiding this technology.

“In other words, we advance this highly effective technology, while at the same time cautioning against its potential dangers. This may seem like a contradiction, but as scientists we are quite proud of our approach, because we believe that this is the very essence of science: we don’t ‘choose sides.’ We examine all aspects of an issue, both positive and negative, and look for answers.”