Extinction of large prey drove evolutionary changes in prehistoric humans, TAU archaeologists say

Prehistoric humans were compelled to produce appropriate hunting weapons and improve their cognitive abilities

Support this researchA new study from the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University (TAU) has found that the extinction of large prey, upon which human nutrition had been based, compelled prehistoric humans to develop improved weapons for hunting small prey, driving evolutionary adaptations. The study reviews the evolution of hunting weapons from wooden-tipped and stone-tipped spears all the way to the sophisticated bow and arrow of a later era, correlating it with changes in prey size and human culture and physiology.

The study was led by TAU’s Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Professor Ran Barkai. The paper was published on August 24, 2023, in Quaternary.

“In the present study, and in our broader unifying hypothesis in general, we propose for the first time an explanation for one of the most intriguing questions in prehistoric archaeology: Why did tools change?” Professor Barkai says. “The usual explanation is that tools changed due to improvements in the cognitive abilities of humans. For instance, when humans were suddenly able to imagine the outcomes of a sophisticated process, they developed a sophisticated stone-knapping method known as the Levallois technique. But one may well ask: Why did humans become smarter all of a sudden? What was the advantage of having a large brain that consumes so much energy?

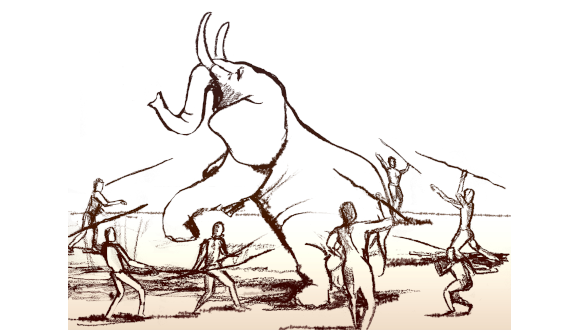

“We demonstrate that these biological and cognitive changes correlate directly with the size of prey. To hunt small elusive animals humans had to become smarter, faster, more focused, more observant, and more collaborative. They had to develop new weapons for hunting from afar and learn how to track their prey. And they had to choose their prey carefully, with preference for high fat content, to ensure a sufficient energetic return — because hunting a large number of agile gazelles requires a much higher investment of energy than hunting one giant elephant.

“This, we propose, is the evolutionary pressure that generated the improvement in human ability and tools — to ensure an adequate energy return on investment (EROI).”

“In the present study we analyzed findings from nine prehistoric sites inhabited during the transition from the Lower to the Middle Stone Age about 300,000 years ago, when Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens first emerged,” Dr. Ben-Dor explains. “In early archaeological sites of this kind, we find mostly animal bones and stone tools used to hunt and process prey. The bones reflect the relative quantities of different species hunted by humans, such as elephants, fallow deer, etc. In this study we looked for a correlation between the advent of stone-tipped spears, and the progressive decline in prey size. Specifically, we examined the emergence of the Levallois technique, which is especially indicative of cognitive development.”

Unlike earlier knapping methods, the Levallois technique first requires the preparation of a core of good-quality stone, then the cutting off of a pointed item off with one stroke, a process that requires the craftsperson to imagine the final outcome in advance. The researchers found that, in all cases and at all sites, stone tips made with the Levallois technology appeared simultaneously with a relative decrease in the quantity of bones of large prey.

Dr. Ben-Dor adds that studies of contemporary hunter-gatherers indicate that a wooden spear is quite sufficient for hunting large prey like an elephant: the hunters first limit the animal’s mobility by driving it into a swamp or a trapping pit, then they thrust the spear into the prey and wait for it to bleed. On the other hand, a middle-sized animal like a deer is much more difficult to trap, and if hit by a wooden spear it will probably run away. A more substantial wound induced by a stone-tipped spear is more likely to slow it down and reduce the distance it can run before it finally collapses, increasing the hunter’s chances of retrieving the fallen prey. Facts about the continual evolution of hunting weapons, necessarily accompanied by improvement of human cognition and skills, have been known for a long time, but a unifying hypothesis for explaining these facts or attributing them to some change in the environment was not proposed. The TAU researchers have tried to address this challenge.

“For the past ten years we have been searching for a unified explanation for focal phenomena in the cultural and biological evolution of prehistoric humans,” Professor Barkai says. “Our excavations at the Qesem Cave site led us to conclude that elephants, a major component of the human diet in our region for a million years, disappeared about 300,000 years ago, as a result of overhunting and climate change. With the huge elephants gone, humans had to find ways for obtaining the same amount of calories from a larger number of smaller animals. Ultimately, we hypothesized that prey size had played a major part in human evolution: at the beginning the largest animals were hunted, and when these were gone humans went on to the next in size, and so on. Finally, when hunting was no longer energetically viable, humans began to domesticate animals and plants. That’s how the agricultural revolution began.”